Regenerative Medicine News and General Information

New Study Finds Special Bone Channels at the Brain’s Border

At the outer border of the brain and spinal cord, immune cells have been observed that originate from the bone marrow of the adjacent skull and vertebrae. They reach this site through special bone channels, without passing through the blood.

There are barriers that protect the neuronal cells from any molecule movement between the blood and the Central nervous system (CNS). These barriers also ensure that the CNS can be kept under surveillance by certain immune cells, but restrict the access of blood-derived immune cells and molecules to specific compartments at the border of the CNS.

Encasing the brain and the spinal cord are three meningeal membranes. The outermost membrane, the dura mater, lacks a blood–brain barrier, and so the entry of blood-derived components, including immune cells, into this layer is unrestricted.

Study Findings

Two new studies studying different subsets of immune cells, myeloid cells of the innate branch of the immune system and B cells of the adaptive immune system. The authors attached the circulatory system of one mouse, in which these subsets of immune cells were fluorescently tagged to that of a second, untreated, mouse, and made the surprising finding that fewer tagged cells than untagged cells were observed in the dura mater of the second mouse.

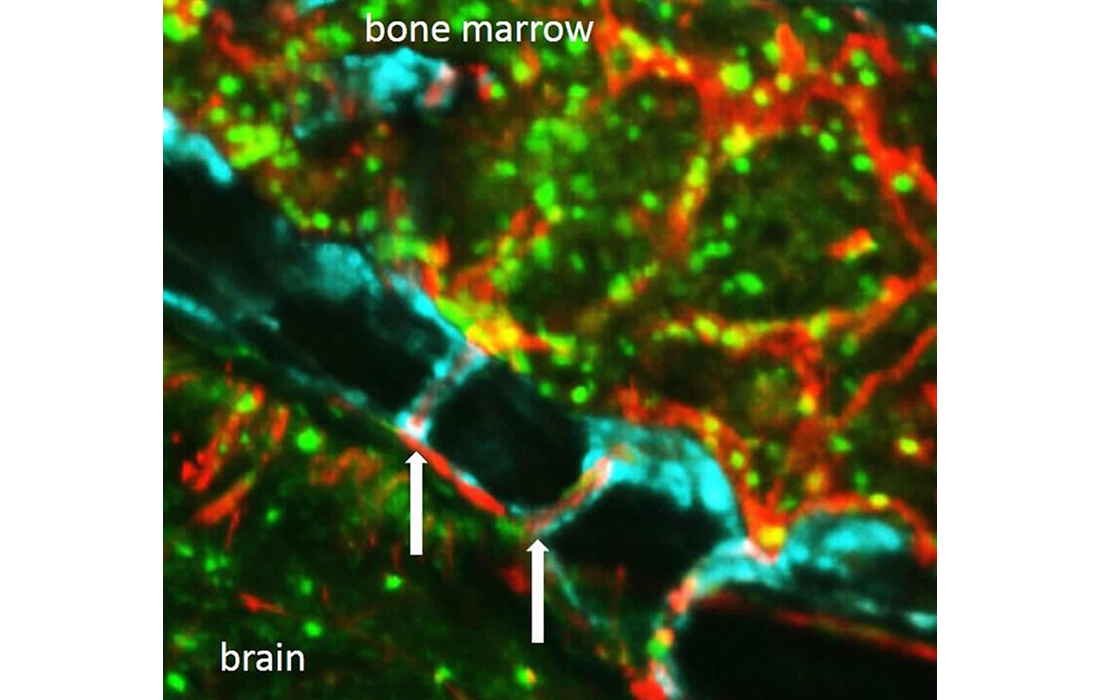

The finding suggests that a considerable proportion of immune cells in the dura mater do not arrive from the bloodstream, but instead originate from the bone marrow in the skull and the vertebrae of the spine. The shortcut is made by the cells crawling along the outside of blood vessels inside small , bony channels, between the bone marrow and the dura mater. Thus, the dura mater sources a private immune protection right outside the outer CNS barrier (the arachnoid mater) from adjacent bone marrow through a previously unrecognized route.

The researchers found evidence that supported the idea that these bone-marrow-derived immune cells are programmed to ensure CNS health, whereas those arriving from the blood tend to be pro-inflammatory and thus more ready to fight potential infections. Moreover, with ageing, increasing numbers of blood-derived immune cells were observed in the dura mater, suggesting a shift in CNS-border immune protection.

They also found a large number of a type of bone-marrow-derived immune cell called granulocytes in the dura mater. These cells are short-lived and circulate the blood and infiltrate tissue only during acute inflammation. Their finding in uninflamed dura mater suggests that these bone-marrow-derived granulocytes might be a special subset of granulocytes with functions different from those of the cells from the blood.

The channels found connecting the skull and vertebra bone marrow with the dura mater also exist in humans, suggesting that observations of immune-cell migration and function in mice might translate to humans.

The results are important in the creation of future therapeutics for conditions such as strokes. Because the dura mater lacks a blood-brain barrier, immune cells there could be more easily targeted than immune cells in the subarachnoid space or in CNS tissue itself.

Source:

Engelhardt B. Private immune protection at the border of the central nervous system. Nature. 2021 Aug;596(7870):38-40. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01962-4. PMID: 34285399.

Image from:

Newly discovered channels in the skull may provide a shortcut for immune cells going to damaged tissue. NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Nahrendorf Lab.